Tell Me About Your Garden Series

Meditation on Matthew 9:35-38 and Ruth 2:1-17

Fifth Sunday in Lent

First Presbyterian Church of Smithtown, NY

Pastor Karen Crawford

April 6, 2025

Listen to the devotion here:

Yesterday, I had a dollop of raspberry jam on my oatmeal for breakfast. And I thought of the gardeners who gave me raspberry jam and jelly—Betsy and Belinda. I was filled with gratitude. Gardeners offered other gifts to me—plants and cuttings so that I could grow my own.

Fresh dried oregano from Belinda and fresh picked figs from Kaitlin’s vine.

Cattie offered cherry tomatoes picked from a plant growing in a pot near her swimming pool.

Jim and I ate butternut squash, eggplant and zucchini, green beans, pickles, peppers, and more—all because of the abundance of the harvest and the generosity of gardeners.

Last summer wasn’t the best harvest for the gardeners in our group. But it wasn’t a bust, either. As Betsy says, “Every year, there are successes and failures.” Reese complained of birds pecking at his tomatoes. Voles tried to wreak havoc in Betsy’s garden. She took to patrolling the area at night to try and protect what was left. Gardeners struggled with deer and rabbit damage, as well.

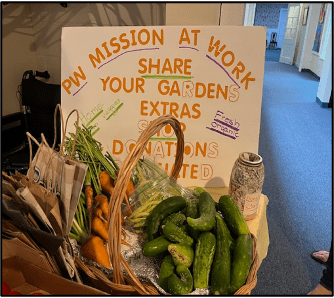

Julie, who provides produce all summer long on our church’s sharing table, says everything was growing pretty good until the flood in August.

Then, her garden was done. Or almost. She brought a bag of garlic to our gardener’s gathering on March 9 and begged us to help ourselves. Now, I have garlic growing in a pot in my dining room window. And every time I water it, I think of Julie and smile. George shares the vegetables he grows in a community garden plot at a Lutheran church with the people in his AA group who meet there. Betsy shares her plants and produce at her work because they always seem so happy when she does.

Reese likes to share with his non-gardening neighbors, especially the children, whom he has invited in previous years to pick pumpkins and pull carrots, just so they could see where carrots come from. “You got to see the kids’ faces when they pull a carrot out of the ground!” he says. “They may never look at a carrot the same way again.”

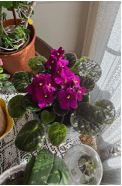

Cattie and Bonnie shared African violets with me that they had propagated themselves. Every time I look at them, I experience anew the joy of receiving their gifts and marvel at the beauty of the purple flowers.

Bonnie helped the children at Smithtown’s homeless shelter last summer plant their own raised garden. She wanted to share not just the produce, but the love of gardening. The shelter harvested tomatoes, she says, and made sauce. One little boy of 7 or 8 told Bonnie that when he grows up, he wants to be a farmer. “That’s my reward,” she says.

Our passage in Ruth today is a window into an ancient society’s harvest practices. What can we learn from them? Ruth, a childless young widow from Moab, has risked her life and future to return to Bethlehem with her Israelite mother-in-law, Naomi, a widow whose sons have died. They have nothing except for Naomi’s kinship ties and the rumor that Bethlehem, consumed by a great famine 10 years before that drove Naomi and her family to live as resident aliens in Moab, now has “bread,” while there is severe famine in Moab, a mountainous region east of the Dead Sea. Ruth and Naomi arrive in Bethlehem just in time for the barley harvest, a sign of God’s providence, indeed, for the harvest would only last a few days.

“The story is set in the period of the Judges “(ca 1200-1020 BC)—the time between Joshua’s death (Judg. 1:1) and the coronation of (the first king of Israel) Saul (1 Sam. 10).”[1] It is an “era of frightful social and religious chaos. The book of Judges teems with violent invasions, apostate religion, unchecked lawlessness, and tribal civil war. These threatened fledgling Israel’s very survival.”[2] And now, added to the social, political, and religious chaos, there’s a famine. “Biblical famines have many natural causes—drought, disease, locust invasions, loss of livestock, and warfare. They were often believed to be God’s judgment.” But the writer of Ruth doesn’t tell us the cause of this famine. Instead, the story points to the biblical pattern for famines—that they often advance God’s plan.

“Judean Bethlehem lay about six miles south of Jerusalem on the eastern ridge of the central mountain range… An ancient town, its name literally means ‘House of Bread.’ Wheat, barley, olives, almonds, and grapes grew abundantly there.[3] When Ruth arrives, she tells her mother-in-law, “I am going to the fields to glean ears of grain behind anyone in whose eyes I find favor.” Why did she need to do this when the right to glean was guaranteed by law?

Leviticus 19:9-10 says, “When you reap the harvest of your land, you shall not reap to the very edges of your field or gather the gleanings of your harvest.You shall not strip your vineyard bare or gather the fallen grapes of your vineyard; you shall leave them for the poor and the alien: I am the Lord your God.”

Likewise, Deut. 24:19-22 says, “When you reap your harvest in your field and forget a sheaf in the field, you shall not go back to get it; it shall be left for the alien, the orphan, and the widow, so that the Lord your God may bless you in all your undertakings. When you beat your olive trees, do not strip what is left; it shall be for the alien, the orphan, and the widow. When you gather the grapes of your vineyard, do not glean what is left; it shall be for the alien, the orphan, and the widow. Remember that you were a slave in the land of Egypt; therefore I am commanding you to do this.” The foundation of these rules is the belief that God is the true landowner. “Israelite farmers might be the means of provision, but the great, compassionate landlord was the actual generous benefactor of the poor.”[4]

But just because laws provide for the feeding of the alien, orphan and widow doesn’t mean that everyone followed them. Owners and reapers were greedy and “often obstructed the efforts of gleaners by ridicule, tricks, and, in some cases, expulsion.”[5] Ruth’s determination to ask permission before gleaning shows that she is a person of “remarkable initiative and courage.”[6] She sets aside fears at being a foreigner and a Moabitess, as the author calls her 5 times. She takes incredible risks to reveal and live out her devotion to Naomi, her faith, and her God. Her plan is to glean ears of grain among the standing stalks. She will follow the reapers, who are not slaves but hired workers, and pick up the ears that are already cut but accidentally drop to the ground. Male reapers grasp the stalk with their left hand and cut off the grain with a sickle in their right. When their arms are full, they lay the stalks in rows beside the standing stalks for women to tie in bundles.

Ruth goes to a field and begins to glean, and “as luck would have it,” she happens upon a piece of farmland belonging to Boaz, who is from the same clan as Naomi’s late husband. Is it luck? Coincidence? Or God’s plan? Boaz arrives—more luck? Coincidence? He greets the workers, “May Yahweh be with you!” He is pronouncing a blessing, saying essentially, “May Yahweh prosper all your efforts with a bountiful harvest!” He is encouraging them that God is with them, “blessing their work.”[7] The people return his greeting with a greeting that was probably “used … at harvest time both to greet…and request God’s provision of a bountiful crop,”[8] “May Yahweh bless you!”

Boaz notices Ruth, asks about her, learns what she has done. He shows unusual grace and kindness, tells her not to glean in any other field and stay close to the other girls. He offers her water whenever she is thirsty and tells the other men not to touch her. She asks why he is being so kind, since she is a foreigner. He answers because of her kindness to her mother-in-law after her own husband died and her willingness to leave her parents and country to come and live with a people whom she does not know. He prays over her. “May Yahweh repay your action, and may your wages be paid in full from Yahweh, the God of Israel, under whose wings you have come to seek refuge.” The image of wings recalls “the protective shield of a bird over its young, an image commonly applied to gods in the ancient Near East …and to Yahweh.”[9]

At the end of the day, Ruth receives much more than she ever expects, being permitted to glean between the sheaves, with the workers pulling out stalks for her to pick up. She harvests until darkness falls and goes home to Naomi with an astounding amount of grain equivalent to at least a half month’s wages for a male worker!

What can we learn from Ruth’s example—as laborers in God’s harvest? First, everyone is wanted and welcome to labor for the Lord, especially the most vulnerable. You don’t have to be strong or rich or a man or a citizen to work for God. She is a foreigner, a childless widow. But she is faithful and loyal to her new kin, her new home, and the God of Israel. Second, workers have different roles but share the same goal: serving the Lord of the Harvest and doing our part to reveal the peaceable Kingdom of God to the world around us.Third, the work for the harvest is characterized by kindness, gratitude, and generosity, and marked by humble prayer, remembering that the fields, the harvest, and the laborers all belong to the Lord.

As we continue our Lenten journey, laboring for Christ’s sake, may the Lord make God’s loving presence known to us. May we be stirred to take refuge under Yahweh’s protective wings in these uncertain times. May the Lord grant us compassion for the world, because people today truly are “harassed and helpless, like sheep without a shepherd.” May we remember to be generous and share with others, praying to the Lord of the Harvest to send out more laborers. For, “The harvest is plentiful, but the laborers are few.”

Lord of the Harvest, you tell us to pray to you and ask you to send out more laborers for your harvest. Thank you for calling us to serve as your laborers, working with the vision and promise of your peaceable Kingdom. Lead us to be kind to one another, like Boaz and Ruth, as we labor. Reveal your loving presence to us and hold us in your protective embrace, in the refuge underneath your wings. Stir our hearts to gratitude for all you have done in Jesus Christ and to compassion for those who are harassed and helpless, like sheep without a shepherd. Amen.

[1] Robert L. Hubbard, Jr., The Book of Ruth (The New International Commentary of the Old Testament) (MI: Eerdman’s Publishing Co.,1988), 84.

[2] Hubbard, The Book of Ruth, 84.

[3] Hubbard, The Book of Ruth, 84.

[4] Hubbard, The Book of Ruth, 136.

[5] Hubbard, The Book of Ruth, 136.

[6] Hubbard, The Book of Ruth, 136.

[7] Hubbard, The Book of Ruth, 144.